Nationalism emerged in Europe which led to the formation of nation-states. The countries formed changed their sense of identity, different symbols, signs, songs etc. started to be associated with communities and countries.

Nationalism in India emerged with colonization. The oppression of the colonizer forged a bond between the oppressed subjects of Raj.

Different communities felt this oppression in unique ways and had to endure it many ramifications, therefore many of them had different notions of freedom.

This bond was used to forge national unity by the Congress but it came with its own conflicts.

World War I : The Beginning of Rebellion

- Since the beginning of World War I in 1914, prices soared in India due to increasing war expenditures by taking war loans and increasing taxes.

- Prices doubled between 1913 and 1918.

- Villages were forced to provide men for recruitment, this generated widespread anger.

- Crop failures between 1918-19 and 1920-21, resulted in acute food shortage, across many parts of India.

- Accompanied with an influenza epidemic, this resulted in the death of 12-13 million people according to the census of 1921.

It was against this backdrop that Gandhi rose as a leader, people’s hopes of the end of their hardship after the end of the war were dashed and that led to rebellion.

Satyagraha

Mahatma Gandhi came to India in January of 1915 from South Africa. He had led a successful protest against the racist, apartheid regime there. He used a new method which he called ‘satyagraha’.

Satyagraha

Meaning “truth force”, or a force born out of truth, peace and love as described by Gandhi. It was a method of resistance which did not involve the use of force or violence.

According to this philosophy, one could win the battle without violence. This could be done by appealing to the conscience of the oppressor.

Both oppressors and the oppressed had to be persuaded to see the truth. Gandhi believed this dharma could unite all Indians.

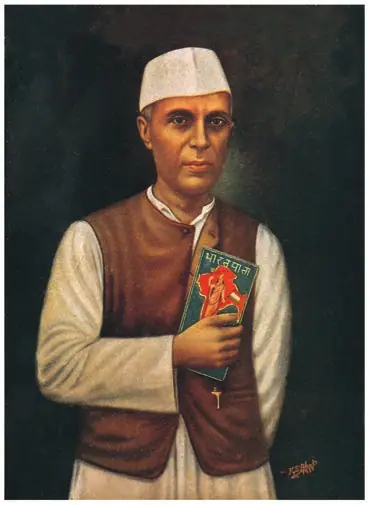

Mahatma Gandhi, 1931.

With satyagraha, Gandhi organized several successful agitations such as :

1. Champaran Satyagraha, 1917.

He inspired the peasants to struggle against the oppressive plantation system for indigo. He also opposed the 3-kathia act, which mandated that farmers had to grow indigo on the 3 parts of the land out of 20 parts.

2. Kheda Satyagraha, 1918.

In order to support the peasants of the Kheda district of Gujarat. Affected by crop failure and a plague epidemic, the peasants of Kheda could not pay the revenue, and were demanding that revenue collection be relaxed.

3. Ahamdaba Mill Strike, 1918.

He organized a satyagraha movement among the cotton mill workers there.

The Rowlatt Act

The Rowlatt Act (1919) was hurriedly passed through the Imperial Legislative Council despite the united opposition of Indian members.

This draconian law gave government powers to:

1. Repress political activities

2. Detention of political prisoners without trial for two years.

Mahatma Gandhi wanted non-violent civil disobedience against such unjust laws, which would start with a hartal on 6 April, 1919.

Many railway workers, factory workers, shops closed down in cities with organized protests. Fearing a popular agitation and damage to railways and communications, the government clamped down hard on protestors.

Local leaders were arrested and Gandhi was barred from entering Delhi.

Jallianwalla Bagh Massacre & The Khilafat Movement

On 13 April, a large crowd gathered at the Jallianwalla Bagh, Amritsar, Pubjab. Some came to protest the government’s crackdown on protesters of the Rowlatt Act, some came for the baisahki fair.

The villagers were unaware of the martial law in place. General Dyer entered the area, blocked the exit points, and opened fire on the crowd, killing hundreds.

He said later, he wanted to “produce a moral effect.”

The massacre ignited widespread protests in north India. This included:

Strikes

Clashes with police

Attacks on government buildings.

Though most of the protests were centered only in the cities. Gandhi knew he had to create movement with a broad base in India. This meant a more inclusive agitation for maximum impact. This could only be done with hindu-muslim unity.

After the war, the Ottoman Empire lost and rumors had it that the king would be forced to accept a harsh treaty. Since he was a spiritual guide to muslims all around the world, this act angered them.

Khilafat Committee was formed in Bombay in March 1919 to defend the Khalifa’s powers.

Muhammad Ali and Shaukat Ali, discussed with Gandhi about the possibility of a united mass action on the issue. Gandhi saw this as an opportunity to bring Muslims under the umbrella of a unified national movement.

In the Kolkata session of Congress in 1920, Gandhi convinced other leaders to support the Khilafat Movement by starting the non-cooperation movement, which was in support of the Khilafat movement and for Swaraj.

The Non-Cooperation Movement (1921-1922)

The Non-Cooperation-Khilafat Movement, spearheaded by Mahatma Gandhi, emerged in response to the Jallianwala Bagh massacre and subsequent British repression.

This movement sought to unify diverse social groups in India, including urban middle classes, rural peasants, and plantation workers, in their struggle against British colonial rule for self-governance (swaraj).

Gandhi argued that British rule survived in India because of India cooperation, that if the India people did not cooperation, the regime would fall within a year.

Genesis of the Movement

- Jallianwala Bagh Massacre: The catalyst for a widespread nationalist resurgence. On April 13, 1919, an unarmed crowd was fired upon by British troops, leading to outrage across India. This incident galvanized public sentiment against colonial rule .

- Khilafat: The treatment of the Khalifa by the British was also used as a tool of protest in non-cooperation, seeking to unite Hindus and Muslims under the same anti-colonial movement.

- Suggestions for Non-Cooperation: Gandhi advocated for a phased approach to non-cooperation, urging Indians to boycott British institutions and relinquish governmental honors .

Urban Middle Classes

- Initially, the movement garnered substantial support from urban areas as people protested through strikes and boycotts of foreign goods .

- The economic effect of non-cooperation was significant.

- Import of foreign cloth halved between 1921 and 1922.

- Khadi was expensive, and easily torn. People could not boycott English cotton mills for too long.

- Boycott of British institutions didn’t work because alternative Indian institutions weren’t available.

- Slowly, due to the lack of Indian institutions, demographics like students and teachers started to attend schools, and lawyers resumed practicing in the courts.

The Countryside

- The Non-Cooperation Movement began in cities but soon spread to rural India.

- It gained momentum by drawing peasants and tribals into its fold, who were facing their own struggles in the years following World War I.

Peasant Struggles in Awadh

In Awadh, peasants, led by Baba Ramchandra, a former indentured laborer, were fighting against oppressive landlords and talukdars.

Key Issues for Peasants:

- Exorbitant rents and additional cesses demanded by landlords.

- Forced begar (unpaid labor) and mandatory work on landlords’ farms.

- Eviction of tenants, leading to insecurity and no right to land.

Demands of the Peasant Movement:

- Reduction of taxes and revenue demands.

- Abolition of begar and oppressive labor practices.

- Social boycott of exploitative landlords (including nai-dhobi bandhs to deny landlords services like barbers and washermen).

Jawaharlal Nehru’s Involvement:

- In June 1920, Nehru began touring Awadh’s villages, speaking with locals to understand their grievances.

- By October 1920, the Oudh Kisan Sabha was founded, with Nehru, Baba Ramchandra, and others leading the movement.

- Over 300 branches of the Oudh Kisan Sabha were set up by the end of 1920.

Challenges of Integration with Congress:

- When the Non-Cooperation Movement launched in 1921, Congress aimed to integrate the Awadh peasant struggle into the broader national movement.

- However, the peasant movement evolved in ways Congress leadership found

difficult to control:

- Violence erupted: Talukdars’ houses were attacked, bazaars looted, and grain hoards seized.

- Rumors spread that Gandhi had declared no taxes were to be paid and land redistributed among the poor.

- The name of Gandhi was used to justify various local actions.

Tribal Peasant Movements

Gudem Hills (Andhra Pradesh)

In the Gudem Hills, tribal peasants experienced a militant guerrilla movement during the early 1920s, which was in conflict with Congress’ non-violent ideology.

Key Grievances:

- Forest closure by the British, preventing access to grazing land, fuelwood, and fruits, severely impacting the livelihoods of hill people.

- Forced begar for road construction further angered the tribal communities.

Leadership of Alluri Sitaram Raju

- Alluri Sitaram Raju, a charismatic leader, claimed to have special powers (astrological predictions, healing abilities, and being immune to bullets ).

- He gained a following by claiming to be an incarnation of God.

- Raju talked about the greatness of Gandhi, promoting khadi and the abandonment of alcohol.

Revolt and Guerrilla Warfare

- Despite his admiration for Gandhi, Raju believed India could only be liberated through force and not non-violence.

- The Gudem rebels attacked police stations, attempted to assassinate British officials, and engaged in guerrilla warfare to achieve swaraj.

Execution:

- Raju was captured and executed in 1924.

- Over time, he became a folk hero and symbol of tribal resistance.

Movement in the Plantations

Freedom for Assam Workers:

For plantation workers in Assam, freedom meant:- The right to move freely in and out of the tea gardens.

- The ability to maintain links with their villages.

The Inland Emigration Act of 1859:

Under this act, plantation workers were not allowed to leave the tea gardens without official permission, and such permissions were rarely granted.The Impact of the Non-Cooperation Movement:

When workers heard about the Non-Cooperation Movement:- Thousands of workers decided to defy authorities.

- They left the plantations and attempted to return to their native villages, believing that under Gandhi’s rule ("Gandhi Raj"), they would be given land in their villages.

The Workers’ Struggle:

- On their way home, workers were stranded due to a railway and steamer strikes.

- They were caught by the police and brutally beaten.

Workers’ Interpretation of Swaraj

Unique Vision of Swaraj:

- The plantation workers, like other groups, had their own understanding of swaraj (freedom).

- They imagined swaraj as a time when all suffering and troubles would be over.

- Their idea of swaraj was not defined by the Congress programme but shaped by their own experiences and needs.

Emotional Connection to the National Struggle:

- Despite their local struggles, when workers and tribals chanted Gandhi’s name and raised slogans for ‘Swatantra Bharat’ (Independent India), they were relating to a national struggle, whose confines were beyond their immediate locality.

Workers’ and tribals’ interpretation of swaraj was deeply personal and local, but their actions also reflected a shared vision of India’s independence, transcending their immediate struggles.

Withdrawal

- In February 1922, Mahatma Gandhi decided to withdraw the Non-Cooperation Movement.

- This was due to internal resistance in the Congress and also because the movement had turned violent in many places.

- Many in the Congress wanted a return to council politics.

- They wanted to participate in elections to the provincial council, set up by the Government of India Act of 1919.

- C. R. Das and Motilal Nehru formed the Swaraj Party within the Congress to argue for a return to council politics. This was opposed by younger leaders such as Bose and Jawaharlal Nehru. They wanted more aggressive mass agitations and full Independence.

- For example, the Chauri Chaura incident that happened in Gorakhpur, 1922. A peaceful demonstration turned into a clash with the police, after which the policemen were burnt alive.

Thus, the movement was halted and eventually called off. However, the political circumstances of the time helped forged another, mass agitation in the image of non-cooperation.

Civil Disobedience

There were two factors that shaped Indian politics moving into the 1920s. They were :

The Worldwide Economic Depression:

- Agricultural prices fell starting in 1926 and collapsed after 1930, leading to widespread economic distress in rural India.

- Peasants struggled to sell their produce and pay taxes, causing turmoil in the countryside.

The Simon Commission (1928):

- The British government of the Tories set up the Simon Commission to review India’s constitutional system, but it included no Indian members, sparking widespread protests.

- The lack of Indian representation in the commission led to the slogan “Go Back Simon” and galvanized national opposition.

In the October 1929, Lord Irwin gave a vague offer of ‘dominion status’ to India in an unspecified future to mollify dissenters. This didn’t satisfy the opposition.

The Lahore Session

Thus, the radicals in the Congress, like Nehru and Bose gained power. The moderate liberals lost their influence. In the December of 1929, under the presidency of Jawaharlal Nehru, the Congress in its Lahore session demanded ‘Purna Swaraj’, that is, full independence.

Jawaharlal Nehru

It was decided that 26 January 1930, would be celebrated as the Independence Day, but it attracted little fanfare which forced the mahatma to relate this abstract concept with real issues.

The Salt March

Gandhi saw salt as a unifying symbol, representing a key commodity consumed by both rich and poor. The tax on salt, alongside the British monopoly, symbolized British oppression.

The movement started on 12 March 1930 and came to an end on 6 April 1930.

Letter to Viceroy Irwin: On 31 January 1930, Gandhi sent a letter to Viceroy Irwin outlining eleven demands, including the abolition of the salt tax. These demands were designed to appeal to a wide spectrum of Indian society.

Ultimatum: Gandhi’s letter served as an ultimatum, warning that if the demands were not met by 11 March, the Congress would begin a civil disobedience campaign.

The Salt March: Gandhi embarked on a 240-mile march from Sabarmati Ashram to Dandi, leading 78 volunteers. The march took 24 days, covering 10 miles per day.

Ceremonial Law Violation: On 6 April 1930, Gandhi reached Dandi and defied British salt laws by making salt from seawater, marking the start of the Civil Disobedience Movement.

Difference from Non-Cooperation: This movement asked people not just to refuse cooperation with the British but also to actively break colonial laws.

Breaking Salt Laws: Thousands across India broke the salt law, made salt, and protested in front of government salt factories. Boycotts of foreign cloth and liquor shops were widespread.

Other Forms of Protest: Peasants refused to pay taxes, village officials resigned, and forest people violated forest laws by collecting wood and grazing cattle in reserved areas.

Government Response and Repression

- Arrests and Violence: The colonial government began arresting Congress

leaders, leading to violent clashes. Notable incidents include:

- Abdul Ghaffar Khan’s Arrest: In Peshawar, angry protests erupted, resulting in many deaths.

- Gandhi’s Arrest: In May 1930, Gandhi’s arrest triggered industrial workers’ protests in Sholapur.

- Repression: The government resorted to brutal repression, with peaceful satyagrahis being attacked, and about 100,000 arrests were made.

Gandhi-Irwin Pact and Aftermath

Gandhi entered a pact with Irwin in March 1931 , agreeing to attend the Round Table Conference in exchange for the release of political prisoners.

- Round Table Conference: Gandhi’s trip to London in December 1931 ended in disappointment when negotiations broke down. Upon his return, repression resumed, and leaders like Ghaffar Khan and Nehru were still in jail.

- Movement Relaunched: Gandhi relaunches the Civil Disobedience Movement in 1932, but it gradually lost momentum by 1934.

Social Groups and Their Participation

Peasants

- Rich Peasants: The Patidars and Jats were hit hard by falling prices and high revenues. They joined the movement, seeking a reduction in revenue demands but became disillusioned when the demands were not addressed in 1931.

- Poor Peasants: Small tenants, burdened by unpaid rent to landlords, joined radical movements for rent remission, often led by socialists and communists. The Congress was reluctant to support these movements since they might offend the business class, causing uncertainty in their relationship.

Business Class

- Initial Support: Indian merchants and industrialists, having gained wealth during WWI, supported the movement for economic freedoms. They helped fund the movement and supported boycotts of foreign goods.

- Declining Enthusiasm: After the failure of the Round Table Conference, industrialists became wary of prolonged disruptions and the rise of socialism within Congress. Their enthusiasm for the movement waned.

Industrial Workers

- Limited Participation: While some industrial workers, especially in Nagpur, participated in the movement, many stayed aloof. However, workers in some areas joined protests against poor working conditions, like strikes by railway and dock workers.

Women’s Participation

- Active Involvement: Women played a significant role, attending marches, boycotting foreign goods, and participating in protests. Many went to jail for their participation.

- Limited Empowerment: Despite their visible presence, women’s roles were still largely symbolic. Gandhi envisioned women as caretakers of the home, and the Congress was reluctant to give them leadership roles.

Challenges and Divisions

Dalits

- Gandhi’s Efforts: Gandhi worked to eliminate untouchability, calling dalits “Harijans” (children of God) and leading campaigns for their rights, including access to public resources.

- Dalit Leaders’ Demands: Some dalit leaders, notably Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, demanded separate electorates and political empowerment, leading to tensions with Gandhi, who believed this would hinder social integration.

- Poona Pact (1932): After a fast unto death by Gandhi, the Poona Pact was signed by both him and B.R. Ambedkar, providing reserved seats for dalits in legislative bodies but with voting rights for the general electorate.

Muslims’ Response

- Alienation: Many Muslims felt alienated after the decline of the Non-Cooperation-Khilafat Movement, worsened by rising Hindu-Muslim tensions and communal riots.

The movement had started at a time when tensions and distrust between Hindus and Muslims were high. The Congress’s association with Hindu nationalist groups like the Hindu Mahasabha deepened Muslim distrust. Efforts to reconcile the Congress and Muslim League failed, as mutual distrust hindered cooperation.

The Birth of a Nation : Nationalism in India

Nationalism thrives when people recognize a shared identity and collective unity. In a country as diverse as India. It emerged through both struggles for independence and cultural processes that shaped people’s imagination.

Bharat Mata

Bharat Mata (Mother India) became the image of India in the early 20th century.

Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay’s Vande Mataram, written in the 1870s, a hymn to the motherland, which was later popularized in the Swadeshi movement.

Abanindranath Tagore painted the famous image of Bharat Mata as an ascetic, divine, and spiritual figure during the Swadeshi movement.

The image of Bharat Mata evolved over time, circulating in prints and becoming a symbol of nationalism.

The Role of Folklore in Nationalism

- Nationalists sought to revive Indian folklore, including ballads, nursery rhymes, and myths, as a way to reconnect with traditional culture.

- Rabindranath Tagore collected folk songs and tales, seeing them as a way to preserve and restore national pride.

- Natesa Sastri’s The Folklore of Southern India, a four-volume collection of Tamil folk tales, which he considered the “most trustworthy manifestation of people’s real thoughts.”

Nationalist Symbols

- Swadeshi Flag (1905) was a tricolour flag (red, green, and yellow) with eight lotuses representing the provinces of British India and a crescent moon for Hindus and Muslims.

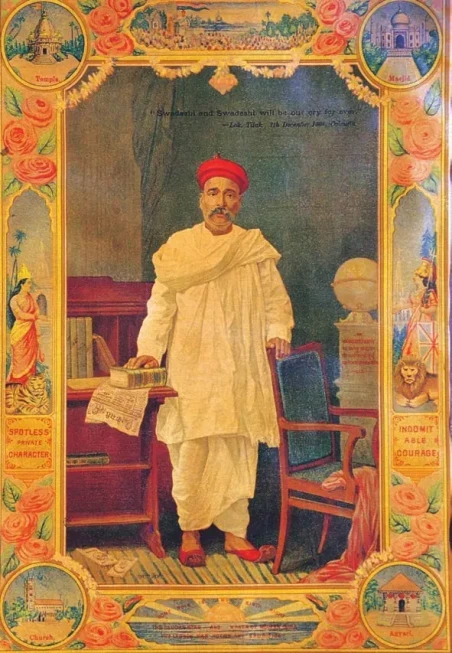

Bal Gangadhar Tilak

- Swaraj Flag (1921): Designed by Gandhiji, this tricolour (red, green, and white) flag had a spinning wheel at its center, symbolizing self-help and independence.

- Carrying and displaying the national flag became a powerful symbol of resistance and nationalism.

Reinterpretation of Indian History

- Nationalists began reinterpreting India’s history to emphasize its achievements in art, science, architecture, culture, and philosophy before British colonization.

- The British portrayal of Indians as backward and incapable of self-rule was challenged by highlighting the general decline after colonization.

- These reinterpretations inspired pride in India’s past and a desire to change the current colonial condition.

Challenges of Unification

- Efforts to glorify India’s past often focused on Hindu achievements and iconography, which alienated people from other communities.

- This selective focus on Hindu traditions led to tensions and a feeling of exclusion among non-Hindu groups, complicating the unification efforts.

By using a combination of cultural symbols, folklore, and history, nationalist leaders aimed to create a unified sense of belonging.

However, these efforts were complicated by the need to accommodate India’s diverse religious and cultural communities.

Conclusion

The freedom struggle, essentially, was a series of highs and lows in terms of national unity. Periods of united action were followed by distrust, alienation and inner conflict. The Congress’ task was to unite the diverse sections of Indian society for a common struggle, doing a balance act and making sure the intrests and demands of one group does not alienat another.

Many groups either completely broke off from the Congress or more conviniently, started selectively adopting some of their ideas. Such as the socialist affiliated workers and farmers.

This gave a signal as to what was to come. A diverse nation, full of different voices, wanting and fighting to be heard.