Nationalism, as a concept, emerged in the 19th century and brought significant political and social changes in Europe.

The formation of nation-states replaced multi-national dynastic empires. The modern state evolved over centuries with centralized power exercising sovereign control over defined territories.

The idea of a nation-state emerged where people developed a collective identity through shared struggles and history.

Frédéric Sorrieu’s Utopian Vision

- French artist Frédéric Sorrieu created a series of four prints visualizing a world of democratic and social republics.

- The first print showcases diverse nationalities paying homage to the Statue of Liberty.

- The shattered remains of absolutist symbols lay on the ground, signifying the fall of autocracy.

- The image portrays fraternity among nations with divine beings symbolizing unity and peace.

Universal Democratic and Social Republic by Sorrieu, 1848.

Ernst Renan’s Definition of a Nation

- In his 1882 lecture, French philosopher Ernst Renan rejected the idea that a nation is based on race, language, or geography.

- Instead, he argued that a nation is a collective will built on shared history, sacrifices, and a common future.

- He emphasized that nations should not annex territories against their will and considered nations as a guarantee of liberty.

The French Revolution and Nationalism

- The French Revolution (1789) marked the first clear expression of nationalism.

- The monarchy was overthrown, and sovereignty transferred to the French citizens.

- The concepts of ‘la patrie’ (fatherland) and ‘le citoyen’ (citizen) reinforced collective national identity.

Measures Taken to Unify France

- Introduction of the tricolor flag.

- Election of the Estates General, renamed as the National Assembly.

- Adoption of a centralized administrative system and uniform laws.

- Abolition of internal customs duties and establishment of a standard system of weights and measures.

- The revolutionary ideas spread to other European countries through Jacobin clubs and military campaigns.

Napoleon and the Spread of Nationalism

Napoleon Bonaparte introduced reforms aimed at rationalizing governance across Europe.

The Civil Code of 1804 (Napoleonic Code):

- Abolished privileges based on birth.

- Established equality before the law.

- Guaranteed the right to property.

His administration abolished feudalism, freed peasants from manorial dues, and improved infrastructure.

Initially welcomed in places like ussels, Mainz, Milan and Warsaw, the French rule became unpopular due to high taxes, censorship, forced conscription and no political freedom.

The Making of Nationalism in Europe

If we look at the map of mid-eighteenth-century Europe we will find that there were no ‘nation-states’ as we know them today. They were ruled by duchies and cantons whose rulers had territorial autonomy.

- Germany, Italy, and Switzerland were divided into multiple kingdoms, duchies, and cantons with autonomous rulers.

- Eastern and Central Europe were ruled by autocratic monarchies, with diverse peoples living within their territories.

- These populations lacked a shared identity or common culture and often spoke different languages.

- The Habsburg Empire (Austria-Hungary) was a mix of various regions and ethnic groups.

- The empire included:

- Alpine regions: Tyrol, Austria, and Sudetenland

- Bohemia: Predominantly German-speaking aristocracy

- Lombardy and Venetia: Italian-speaking provinces

- Hungary: Half spoke Magyar, the other half various dialects

- Galicia: Polish-speaking aristocracy

- Other ethnic groups: Bohemians, Slovaks, Slovenes, Croats, and Roumans

- Political unity was difficult due to these differences.

- The only unifying factor was allegiance to the emperor.

Social Hierarchy

- The aristocracy was dominant but numerically small.

- The peasantry formed the majority but lacked privileges.

- In western Europe, the bulk of the land was farmed by tenants and small owners, while in Eastern and Central Europe the pattern of landholding was characterised by vast estates which were cultivated by serfs.

- Industrialization started in England from the mid-eighteenth century, while in places like France and Germany it came only in the nineteenth

- Industrialization created a new middle class of businessmen, professionals, and industrial workers whose existence was based on production for the market.

- Due to Industrialization to a lesser extent, these liberal middle class populations were smaller.

These populations formed the back of the democratic republican movement that was to sweep across Europe.

Liberal Nationalism

- National unity in early 19th-century Europe was closely tied to liberalism.

- The term liberalism comes from the Latin liber (free) and stood for:

- Individual freedom

- Equality before the law

- Government by consent

- End of autocracy and clerical privileges

- Constitutional and parliamentary governance

- Protection of private property

- Liberalism did not mean universal suffrage:

- In revolutionary France, voting rights were limited to property-owning men.

- Women and non-propertied men were excluded from political participation.

- The Napoleonic Code reinforced these restrictions, reducing women’s status.

- Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, women and non-propertied men fought for political rights.

- Economic liberalism supported:

- Free markets

- Abolition of state-imposed trade restrictions

- Economic fragmentation in German-speaking regions:

- Early 19th century: 39 states, each with its own currency, weights, and measures.

- Trade barriers caused inefficiencies, with high customs duties and inconsistent measurements.

- Zollverein (1834):

- A customs union initiated by Prussia, joined by most German states.

- Abolished tariff barriers and reduced currencies from over 30 to 2.

- Railways boosted mobility and economic integration.

- Economic nationalism fueled the broader movement for national unification.

Conservatism After 1815

Post-1815 Europe was dominated by conservatism:

- Conservatives aimed to preserve traditional institutions like the monarchy, Church, social hierarchies, property, and family.

- However, they accepted that modernization (stronger state power, modern army, efficient bureaucracy, abolition of feudalism) could reinforce monarchy.

Congress of Vienna (1815):

- European powers (Britain, Russia, Prussia, Austria) met to redraw Europe’s map after Napoleon’s defeat.

- Led by Austrian Chancellor Metternich, the Treaty of Vienna (1815) aimed to undo Napoleon’s changes.

- Key outcomes:

- Bourbon dynasty restored in France.

- France lost annexed territories.

- Buffer states created to prevent future French expansion:

- Kingdom of the Netherlands (including Belgium) in the north.

- Genoa added to Piedmont in the south.

- Prussia gained new western territories; Austria took control of northern Italy.

- Russia got part of Poland; Prussia got part of Saxony.

- German Confederation (39 states) remained unchanged.

- The goal was to restore monarchies and enforce a conservative order.

Conservative regimes post-1815:

- Autocratic rule: no tolerance for dissent or criticism.

- Censorship laws restricted newspapers, books, plays, and songs promoting liberty and revolution.

- Despite repression, liberal-nationalists opposed the conservative order, particularly demanding freedom of the press.

The Revolutionaries and Secret Societies

- Repressive conservative regimes led to the formation of secret societies advocating nationalism and democracy.

- Born in 1805, Giuseppe Mazzini founded Young Italy and Young Europe, envisioning a unified republican Italy. As a young man of 24, he was sent into exile in 1831 for attempting a revolution in Liguria.

- Following his model, secret societies were set up in Germany, France, Switzerland and Poland. Mazzini’s relentless opposition to monarchy and his vision of democratic republics frightened the conservatives.

- Metternich labeled Mazzini “the most dangerous enemy of our social order.”

The Age of Revolutions: 1830-1848

Nationalist Uprisings

- Nationalist uprisings erupted across Europe.

- The July Revolution (1830) in France led to the overthrow of the Bourbon monarchy. It was replaced by a constitutional monarchy with Louis Philippe as its head.

- Philippe’s rule was popularly known as the July monarchy, but as economic conditions worsened, he had to abdicate his throne in 1848.

- The July Revolution sparked an uprising in Brussels which led to Belgium breaking away from the United Kingdom of the Netherlands.

One way European nationalism manifested was the Greek war of independence, a struggle against the Ottoman Empire. Lauded as the cradle of European civilization, Greece received sympathy among the European public. Greece gained independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1832.

Romanticism and Nationalism

Artists and poets emphasized emotions, folklore, and shared heritage to inspire nationalism. They were generally critical of the glorification of science and reason.

The German philosopher Johann Gottfried Herder (1744-1803) claimed that true German culture was to be discovered among the common people – das volk.

The Grimm Brothers collected German folktales to promote national identity.

The Polish struggle against Russian rule used language and religious instruction as tools of resistance.

In 1831, an armed rebellion against Russian rule took place which was ultimately crushed. Many members of the clergy in Poland began to use language as a weapon of national resistance. Polish was used for Church gatherings and all religious instruction.

Economic Hardships and Uprisings

Economic hardship in the 1830s:

- Rapid population growth led to high unemployment.

- Rural migration to cities caused overcrowding and slums.

- Small producers struggled against cheap machine-made imports from England, especially in textiles.

- Peasants faced feudal dues in aristocratic regions.

- Food shortages and poor harvests led to widespread poverty.

1848 Revolutions in Paris:

- Economic crisis led to protests and barricades.

- King Louis Philippe fled.

- A Republic was proclaimed by the National Assembly.

- Suffrage granted to all adult males (21+).

- Right to work guaranteed; national workshops established for employment.

1845 Silesian Weavers’ Revolt:

- Weavers suffered as contractors reduced payments despite extreme poverty.

- June 4, 1845: Weavers marched to demand higher wages but were ignored.

- Protest turned violent—homes, furniture, and warehouses were destroyed.

- The contractor fled, but later returned with the army.

- Eleven weavers were shot in the ensuing crackdown.

The Unification of Germany and Italy

There is a large backdrop against which this unification happened. Cycles of revolt and repression kept on going in large parts of Europe from 1830s to early 1850s. Liberal movements frequently lost their social base because they were composed of the middle-class who frequently resisted the demands of the workers.

In 1848, food shortages and widespread unemployment brought the population of Paris out on the roads. Barricades were erected and Louis Philippe was forced to flee.

Earlier, in 1845, weavers in Silesia had led a revolt against contractors who took advantage of widespread unemployment and reduced the wages of the weavers. This was eventually crushed by the army. 11 weavers were shot.

The middle class tried to use the popular unrest to make their demand of a nation-state run by parliamentary principles of universal suffrage,freedom of the press and freedom of association.

On 18 May 1848, 831 elected representatives marched in a festive procession to take their places in the Frankfurt parliament convened in the Church of St Paul. Their demand of a parliamentary monarchy was rejected by the Prussian monarch Friedrich Wilhelm IV.

They were forced to disband by the army.

As you might’ve noticed, there was emerging on the continent, a cycle of revolt and repression. But you aren’t the only ones to notice this. European monarchs realized that liberal movements could not be suppressed forever. So they made concessions.

In the years after 1848, the autocratic monarchies of Central and Eastern Europe began to introduce the changes that had already taken place in Western Europe before 1815.

Thus serfdom and bonded labour were abolished both in the Habsburg dominions and in Russia.

The Habsburg rulers granted more autonomy to the Hungarians in 1867.

Germany

After 1848, the idea of nationalism moved away from democracy and revolution. Conservatives used nationalism to strengthen state power and political dominance.

1848: Middle-class Germans attempted to unify Germany under a liberal, parliamentary system, but were suppressed by monarchy, military, and Junkers (Prussian landowners).

Prussia took leadership of unification under Otto von Bismarck.

Three wars (Austria, Denmark, France) (1864–1871) led to Prussian victory and unification.

Proclamation of the German Empire (1871):

- 18 January 1871: Kaiser William I of Prussia was proclaimed German Emperor at Versailles’ Hall of Mirrors.

- Attended by German princes, army representatives, and Prussian ministers, including Bismarck.

Unified Germany, 1866-71.

- Post-unification reforms:

- Prussia dominated the new German state.

- Focus on modernizing currency, banking, legal, and judicial systems.

- Prussian policies became a model for the rest of Germany.

Italy

- Italy was fragmented into multiple states controlled by Austria in the north, the Pope in the center, and Spanish Bourbon kings in the south.

- Italian was still fragmented into multiple dialects and was yet to acquire its modern form.

- Giuseppe Mazzini and Young Italy propagated nationalist ideas.

- Count Cavour of Sardinia-Piedmont led diplomatic and military efforts for unification for his King Victor Emmanuel II. He was a french-speaking Italian elite who sought a unified Italy for economic reasons rather than democratic.

Animated unification of Italy.

- With France’s support they defeated the Austrian forces.

- Giuseppe Garibaldi’s Red Shirts successfully liberated southern Italy.

- In 1870, Italy was unified with Rome as its capital. However, the largely illiterate Italian population was unaware of liberal nationalist ideas.

Curious Case of Britain

Formation of the British Nation-State:

- Not due to revolution, but a gradual process.

- Before the 18th century, people identified as English, Welsh, Scot, or Irish rather than British.

- The English nation grew in power and wealth, extending its influence over other ethnic groups.

England’s Domination Over Scotland:

- 1688: English parliament seized power from the monarchy.

- Act of Union (1707): Created the United Kingdom of Great Britain, effectively making Scotland subordinate to England.

- Scottish culture suppressed (Gaelic language banned, national dress forbidden).

- Scottish Highlanders faced repression and were forcibly displaced.

English Control Over Ireland:

- Ireland was deeply divided between Catholics and Protestants.

- English-backed Protestants dominated over the Catholic majority.

- 1798: Catholic revolt led by Wolfe Tone and the United Irishmen failed.

- 1801: Ireland was forcibly incorporated into the UK.

Creation of a “British” Identity:

- English culture became dominant.

- British flag (Union Jack), national anthem (God Save Our Noble King), and English language were promoted.

- Other nations became subordinate partners within Britain.

Visualizing the Nation

Artists in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries found a way out by personifying a nation. Thus they made the female figure an allegory of the nation.

Personification of Nations

France: Marianne, symbolizing liberty and unity.

Germany: Germania, depicted with an oak wreath and breastplate.

Painting of Germania, the personification of the German nation-state.

Artistic depictions reinforced nationalistic sentiments.

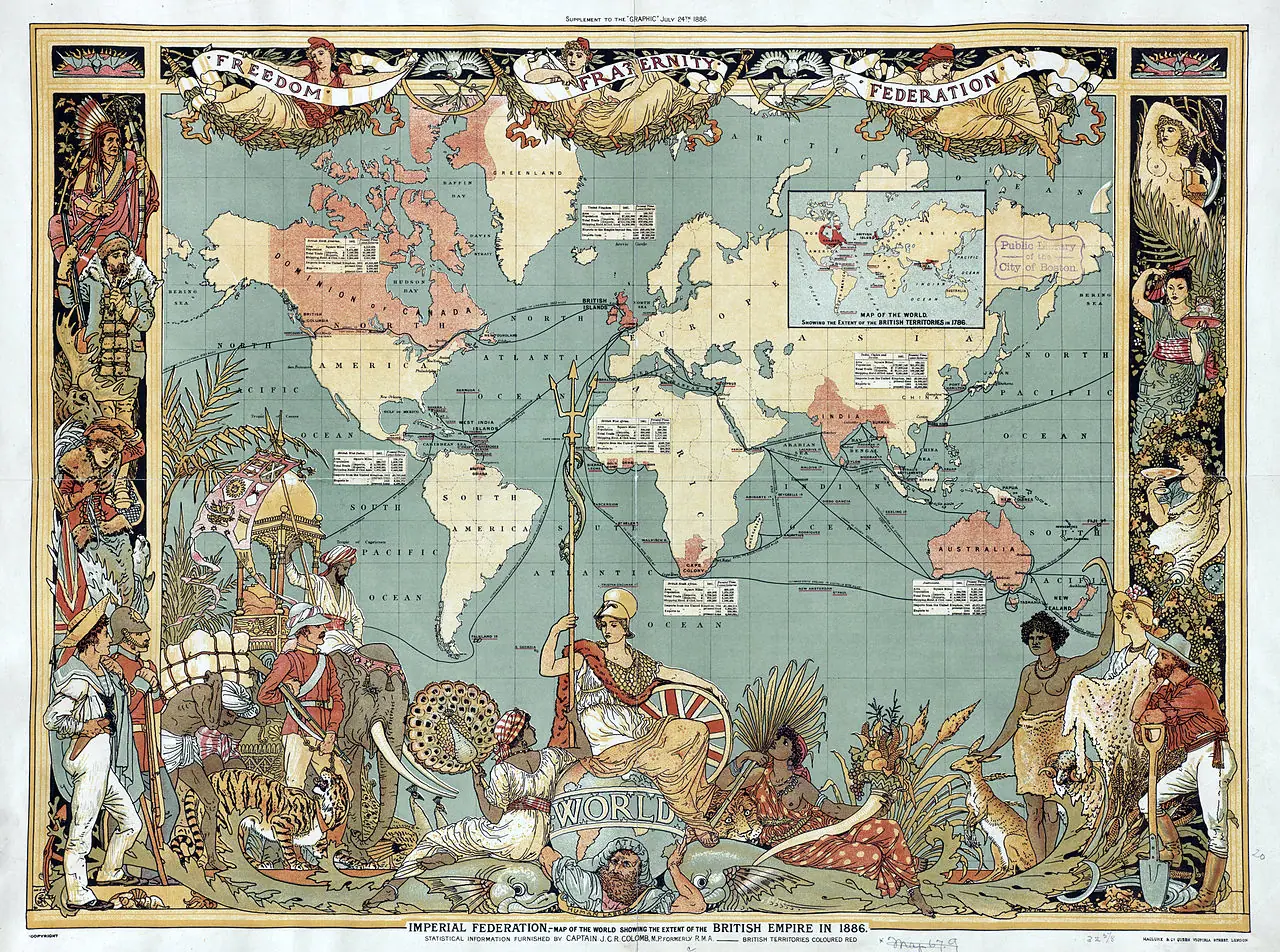

Nationalism and Imperialism

Transformation of Nationalism:

- Initially tied to liberal-democratic ideals, but by the late 19th century, it became narrow, aggressive, and militaristic.

- Nationalist groups became intolerant, leading to increased conflicts.

- Major European powers exploited nationalist sentiments to further their imperialist ambitions.

Imperial Federation, Map of the World Showing the Extent of the British Empire in 1886.

Balkan Nationalism and Conflict:

- The Balkans included modern-day Romania, Bulgaria, Albania, Greece, Macedonia, Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Slovenia, Serbia, and Montenegro.

- These regions were part of the weakening Ottoman Empire.

- Inspired by romantic nationalism, Balkan nations sought independence, using history to justify their claims.

- However, Balkan states fought among themselves for territory, creating regional instability.

Great Power Rivalry in the Balkans:

- European powers (Russia, Germany, Britain, Austro-Hungary) competed for influence in the Balkans.

- The region became a flashpoint for conflicts, eventually contributing to World War I (1914).

Nationalism and Anti-Imperialism:

- While nationalism fueled European conflicts, it also inspired anti-colonial movements worldwide.

- Colonized nations sought independence and self-rule, adapting nationalism to their unique contexts.

- The concept of nation-states became widely accepted as the ideal form of political organization.

Conclusion

Nationalism emerged as a revolutionary force, challenging monarchies and colonial rule. It sought to bring liberal democratic reforms with the basis of such a government being a nation.

It started from middle-class’ desire for greater autonomy and freedom—both political and social. However, it was weaponed by conservative forces for imperialist causes and conquest. It played a very crucial role in the unification and formation of nation-states in Europe.

However, the shift from liberal nationalism to aggressive nationalism had profound global consequences like democratic backsliding and suppression of dissent.

Eventually, the cycle of nationalist repression gave way to the realization of actual political freedom for the masses, but still the middle-class got to enjoy their rights far more than the peasants.